The Legacy of Swiss Philhellenism

The crucial influence of Ioannis Kapodistrias in the formation of an independent and neutral Switzerland, as well as the strong participation of Swiss Philhellenes in the Greek fight for independence lead to strong ties between the two developing nation states and sustained good relations in the centuries to come.

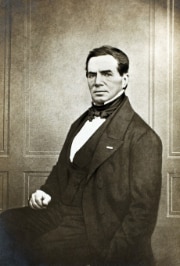

Jean Gabriel Eynard continued to assist the incipient Greek state by attempting to constitute a Swiss Guard at its service, in order to serve the new government, or by cofounding the Greek National Bank in 1841.

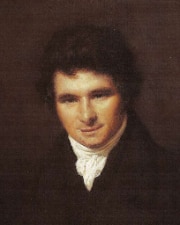

A young Swiss theologian and philologist, Élie-Ami Bétant, became secretary to Kapodistrias in 1827, would later on support the insurrection against the Ottomans on Crete in 1866, by organizing the “Crete Committee” and become General Consul of Greece in Switzerland by order of King Georges I.

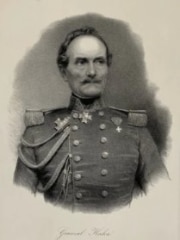

Emanuel Amenäus Hahn, originally from Ostermundigen, dedicated a big part of his life to military service in the Greek Army, ending up as lieutenant general and right hand man of Greece’s first King Otto.

Following in the footsteps of their father and father-in-law,Emmanuel von Fellenberg, his descendants bought the estate Achmetaga on Northern Evia, the second largest Greek island with some similarities to Swiss topography, in order to export the pedagogical concepts developed at his agricultural school in Fellenberg, Hofwyl, to Greece.

In the world of culture and research, a more grounded exploration of the reality of Greek life, beyond the romantic notions conceived by reading the sources of antiquity, lead to a more realistic appreciation of the country and its history. Several reputable Swiss scientists and archeologist have been inspired by their philhellenic experience during the 19th century, such as anthropologist Johann-Jakob Bachofen, (1815-1887), art historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897) or famous symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901).