Q&As on international humanitarian law

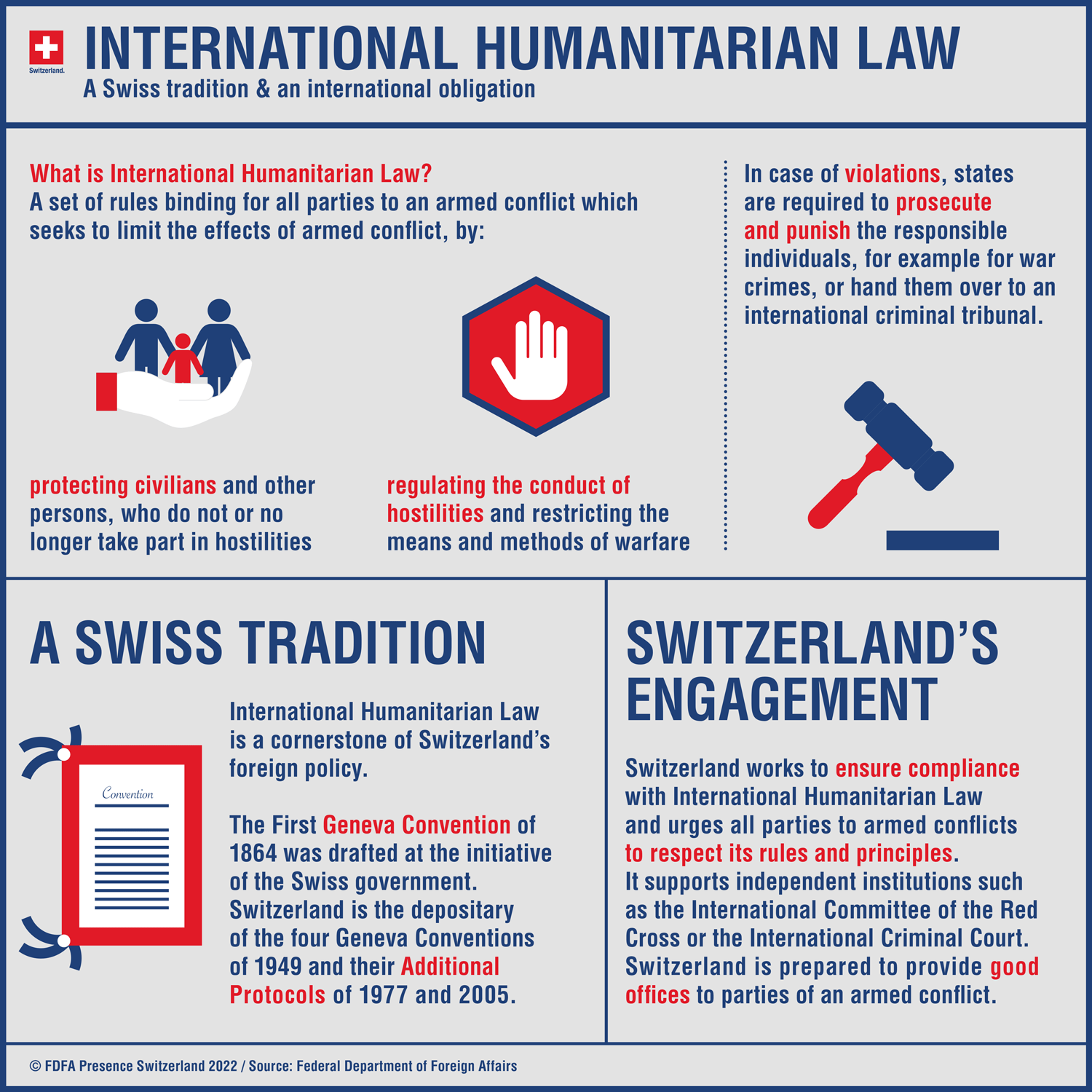

Armed conflicts increases the use of terms that are closely related to international humanitarian law, such as the Geneva Conventions and war crimes. International humanitarian law, also known as the law of armed conflict or the law of war (ius in bello), applies only in armed conflicts and has two functions: it regulates the conduct of hostilities on the one hand and protects the victims of armed conflicts on the other. Q&As.

International humanitarian law governs the conduct of war in armed conflicts and protects civilians. © Keystone

When does international humanitarian law apply?

International humanitarian law is applicable in armed conflicts. Although none of the relevant conventions contains a definition of armed conflict, it has been described as follows in jurisprudence: “an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed forces between States or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organised armed groups or between such groups within a State.” Thus armed conflicts can be international or non-international. To qualify as such a non-international armed conflict must reach a certain intensity and the armed group(s) must be organised to a certain degree. Internal tensions, internal disturbances such as riots, isolated or sporadic acts of violence and similar events are not covered by international humanitarian law.

How does international humanitarian law govern the conduct of war?

Not all means and methods of warfare are allowed in an armed conflict. International humanitarian law stipulates the military operations, tactics and weapons permitted. The two generally accepted principles of distinction and proportionality are the basis for a number of specific rules such as prohibition of direct attacks on the civilian population or on civilian objects, prohibition of indiscriminate attacks and the obligation to adopt precautionary measures (precaution) so as to avoid or limit casualties among civilians and damage to civilian objects to the greatest possible extent.

Why are the Geneva Conventions central to international humanitarian law?

After the Second World War, states agreed to introduce more stringent rules for the effective protection of persons who are not, or no longer, taking part in hostilities. The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and their Additional Protocols of 1977 and 2005 are the cornerstones of international humanitarian law. They are supplemented by other treaties and customary international law, which prohibit or restrict the use of means and methods of warfare and protect certain categories of persons and objects.

Who do the Geneva Conventions protect?

In accordance with the Geneva Conventions of 1949 persons who have a right to special protection are considered “protected persons”. They include the wounded, sick and shipwrecked, prisoners of war, civilians on the territory of the enemy and under its control, and civilians in an occupied territory. The following are usually counted as protected persons: medical and religious personnel, aid and civil protection staff, foreigners, refugees and stateless persons on the territory of a party to the conflict, as well as women and children.

How does international humanitarian law specifically help to protect civilians from starvation in armed conflicts and to have access to medical care?

If the civilian population is not adequately provided with food supplies, international humanitarian law provides that relief actions which are humanitarian, impartial and non-discriminatory shall be undertaken, subject to the consent of the parties concerned. Exceptions to this consent proviso are situations of occupation in which the occupying force is obliged to accept humanitarian relief. It also requires states to allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded access of relief consignments. Civilians may turn to any organisation that could come to their aid. Despite this, humanitarian organisations often have no access to civilians in need of assistance and protection in armed conflicts, either because parties to the conflict refuse permission, or because of geographical or logistical difficulties, bureaucratic obstacles or security considerations.

Armed conflicts threaten children in particular. How does international humanitarian law protect children?

International humanitarian law offers special protection to children. Parties to a conflict are under obligation to provide all the care and assistance that they need due to their youth or for any other reason. Food and medical aid must be provided to children before others. International humanitarian law also contains special guarantees for detained children, the inviolability of their nationality and civil status and for reunification with their families. Children orphaned by war or separated from their parents have the right to education in accordance with their own religion and culture.

And women?

International humanitarian law calls for special protection of women. As civilians they are protected against any assault on their honour and physical integrity. Pregnant women and mothers of small children enjoy the same status as the sick and wounded, being transferred to safety zones and are first in line for assistance. Other special provisions protect women who are members of the armed forces, for example, in the case of women who are prisoners of war, who are to be housed separately from men and are to be placed under the direct supervision of other women.

What challenges does international humanitarian law face today?

The global fight against terrorism, the growing phenomena of the direct participation in hostilities of civilians, increase in the number of non-state actors involved in conflicts, as well as technological developments are only some challenges that international humanitarian law must face nowadays. Although the existing rules of international humanitarian law suffice to respond to these challenges, implementation of these rules is still incomplete. Therefore, it is important that the actors concerned ensure a higher degree of respect for international humanitarian law and its implementation, in particular through reaffirmation and dissemination of existing rules as well as through further clarification of some of them.

Is international humanitarian law still relevant in the context of digitalisation?

In today’s world, technological advances have given rise to new means and methods of warfare, such as cyber means and greater integration of autonomous components in weapons systems. For Switzerland, there is no doubt that international humanitarian law applies to these new weapons and to the use of new technologies in war. The challenge lies in knowing how they can be used in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law. Switzerland is actively involved in the work of various forums to help clarify these issues.

What is meant by war crimes?

War crimes are grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 protecting persons and objects as well as other serious violations of the laws and customs that apply to an international or non-international armed conflict. War crimes include notably: wilful killing, torture, deportation, ill treatment, unlawful detention, hostage taking, wilful attacks against civilians and against civilian objectives, recruitment of children in armed forces, and pillage.

How are war crimes prosecuted?

States are under an obligation to prosecute or extradite persons suspected of having committed war crimes on their territory. In parallel, the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague prosecutes individuals for the most serious crimes of international concern: crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and crime of aggression. The ICC plays a complementary role, i.e., it only steps in once it becomes clear that the national authorities primarily responsible for prosecution are either unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the necessary investigation and prosecution.